Yavuz Gallery is pleased to present Some Deaths Can’t Be Buried, a solo exhibition by leading Thai artist Thasnai Sethaseree.

In Thailand, myths and formalistic aspects of contemporary art embellish new seductive forms of totalitarianism. The Thai authoritarian state utilises aesthetic concepts as a political project by reducing the political potential and motivation of works of art to works of moral ambiguity. Accordingly, these artworks aestheticise violence and turn contemporary political and social toxicity into an object of fascination. This sort of artwork, usually about harmony, order, and contemplation, tends to serve the disinterested, or is experienced in a manner of disinterestedness and therefore reinforces the ideas of ethics, social solidarity, and political passivity. Among other things, the concepts about beauty and order are collapsed into each other. They refer to the virtuous spectators whose lives are dismissive of social brutality and unjustness. Therefore, people’s sensus communis and their perceptual experiences of beauty make themselves passive spectators to the troubles of their immediate social world. The use of aesthetics in this sense ensures that works of art and their ceremonious activities buttress the superiority of the alchemical power of the Thai state.

Sethaseree’s Some Deaths Can’t Be Buried explores an interrelation between these concepts of aesthetics and totalitarianism. The significant forms of this interrelation mediate between the spectacular conditions of the aesthetic events and the intensity of people’s feelings and experiences so as to reconcile differences and political disagreements.

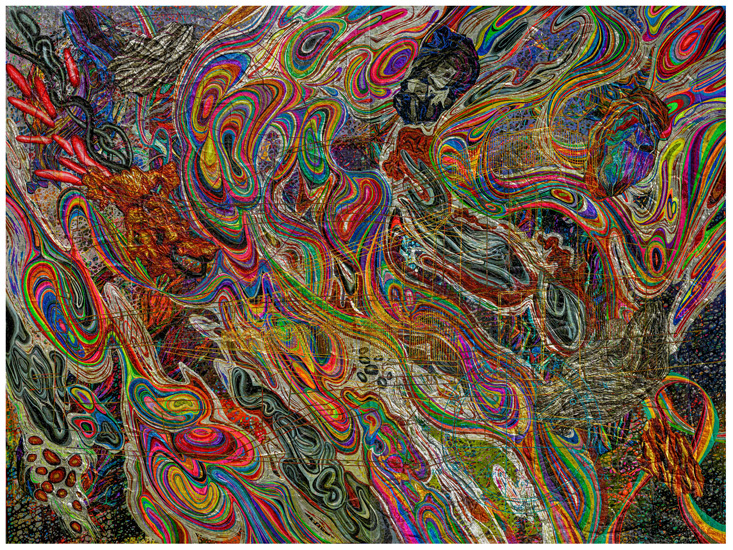

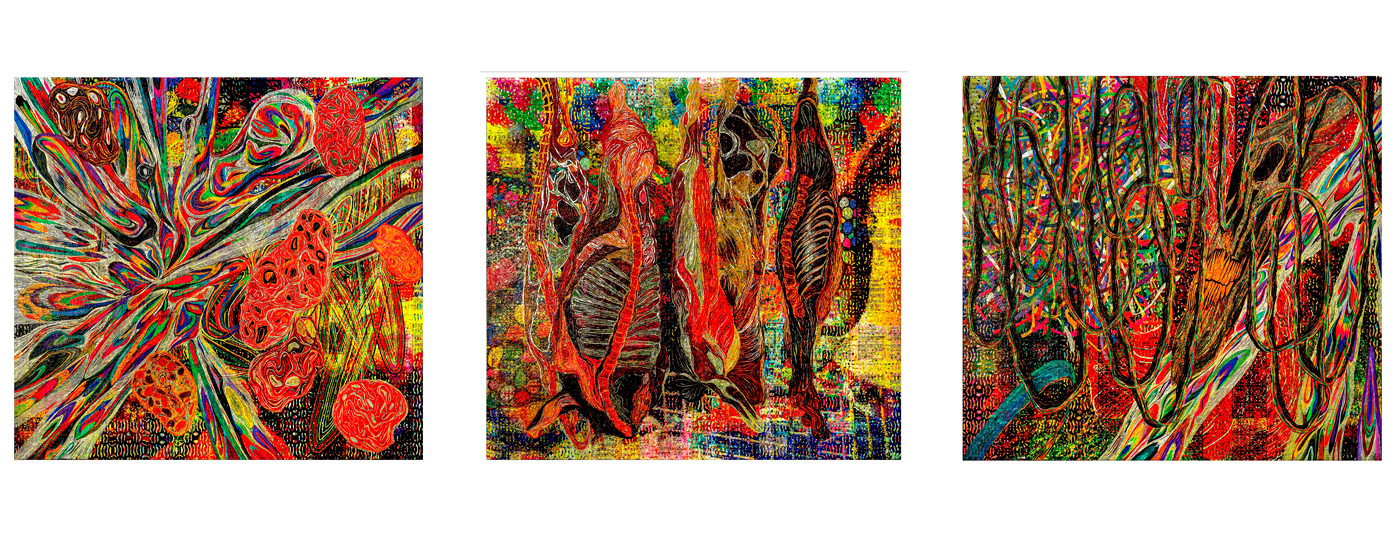

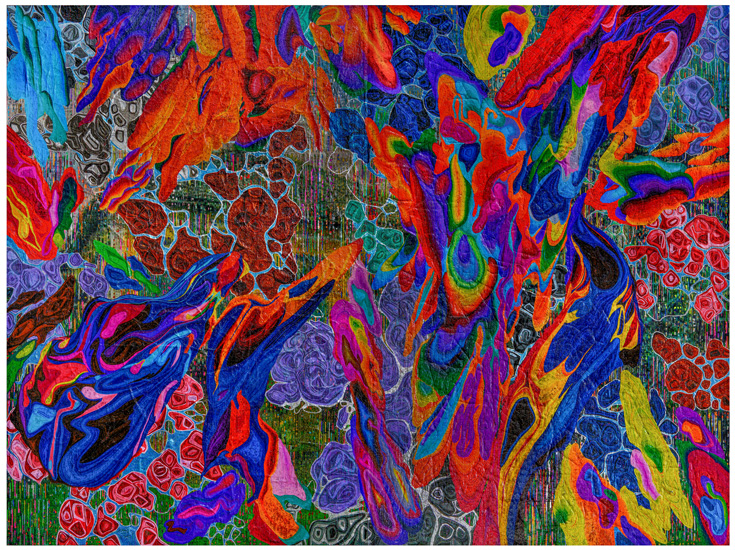

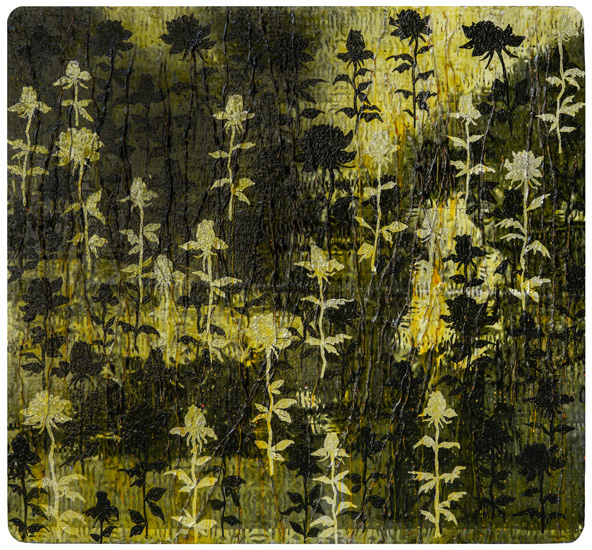

For three pieces of Sethaseree’s museum series, archival photographs of state-run museums are used as the background: Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, National Gallery, and Ratchadamnoen Contemporary Art Center. In addition, tropical pitcher plants indicate the number of 99 dead people who were killed by Thai soldiers in 2010; a sky map and an astrological drawing on the date of coup d’état in 2006; images of gemstones, natural copper, mercury (quicksilver), and Ethyl Alcohol alternately are juxtaposed, overlapped, and rest atop the pieces appearing suspended in a fluid and fermenting condition. Those elements construct complex layers in one piece — together with scientific diagrams of tumours, images of cancer cells and germs invading the middle of the frames as biological infection in other pieces — that stage an encounter between solidity and fluidity, order and improvisation, density and deficiency, the sacred and the profane. While in a large triptych, cattle carcasses hung in the middle frame above images of Christmas and New Year’s celebrations suggest a psychological mixture of Thai politics and its historiography that straddle between concepts of animism and modernity.

Outline drawings of the old prison, Mahantapai Prison, and a new shopping mall, Icon Siam, also emerge on the surface details of the works. The prison was built during the era of Thai absolute Monarchy, King Rama the Fifth and later turned into a museum, known as The Corrections Museum today. Visitors look at the torture machines, executions and residues of dead prisoners — a horrifying past turned to spectacle. In the same manner, the Icon Siam was recently built in the Thai Crown Property area, and its architectural aspect implies a sense of phantasmagoria that produces hallucination through an accomplishment of the aestheticisation of politics. Through the art of decoration and ornament, the imaginary of this shopping mall buries social reality and eliminates the condition of pain and suffering, making people feel miniscule and fearful of authoritarian domination, whilst embracing the theatrical aspect of living death, the alienation of the senses, and the annihilation with enjoyment.

What Sethaseree sees is a sense of melancholy that permeates between the layers of the works, the layers of politics and everyday life. It is a kind of distressing form in Thai society today that forces things to seem impossible to co-exist and be integrated firmly. For the artist, this is the art that is not just only made by virtue of enhancing the aesthetic circumstance of Thai politics, but ensuring the social order and the political superiority to become real and undeniable. Its formation consolidates disinterested pleasure with misery and transforms the concept of totalitarianism surprisingly into visual magnificence and splendour.