The land refuses to be beautiful—not because beauty is absent, but because it has too often been demanded. Demanded as surface, as harmony, as image, as proof of order. This refusal is not a rejection of care, but a resistance to a way of seeing that smooths over damage, contradiction, and belief. It holds together histories and the present as overlapping inscriptions, where what is written never fully replaces what came before. In this sense, the land speaks through layers rather than declarations, through friction rather than resolution—asking not to be admired, but to be read.

The Land that Refuses to be Beautiful traces the quiet structures that shape perception—between land and ownership, belief and representation, beauty and extraction. Rarely formalised, these structures continue to govern how landscapes are framed, how cultures are aestheticised, and how certain ways of seeing are normalised while others are marginalised. What remains today is not clarity but a layered, and unstable field.

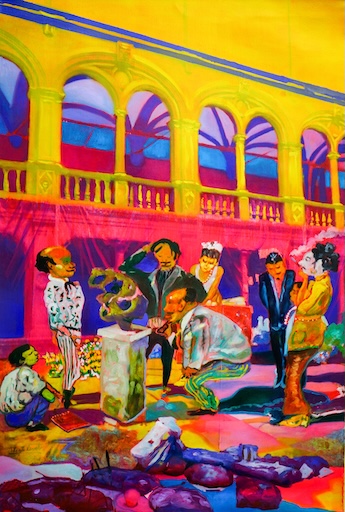

My practice draws from the Indonesian notion of lukis, understood not simply as painting-as-object, but as a situated praxis—a way of making images that is entangled with ritual, labour, spirituality, and everyday life. Painting becomes a method of reading and rewriting: working over surfaces that already carry histories, ideologies, and desires. Images are borrowed, overlaid, obscured, and disturbed, allowing contradictions to remain visible rather than resolved. It is shaped by my physical journey between Bandung, Ciamis, and now Melbourne; between studio, archive, ritual site, and domestic space. Lukis is inseparable from my family history, from stories inherited through my parents, from moments of return to ancestral land, and from the slow realisation that the personal is never outside the political. Even belief—often treated as private—carries historical weight.

Many of the works are drawn from images found in both personal and public archives: colonial postcards, art historical reproductions, political banners, site photographs, fragments of my own past. I print them at full scale using billboard techniques familiar from Indonesian streets, then paint over them—guided not only by reason, but by feeling and faith. This process is not about mastery. It is about staying accountable to what I touch. Each surface becomes a site of accumulation, not correction.

The decimated surface speaks to histories that have been damaged but not erased. These inherited structures persist through habit, silence, and repetition: colonial visual regimes, classed aesthetics, inherited privilege—including my own position within them. I do not approach these structures from a distance. I approach them from inside, acknowledging complicity as a necessary condition of working through them.

The colour in my work, which is often considered excessive or improper, functions as both refusal and care. It disrupts colonial harmony, challenges cultivated restraint, and insists on other modes of seeing rooted in community, ritual, and survival. My works ask the viewer to hesitate, to move, and to read slowly rather than simply consume.

The Land that Refuses to be Beautiful proposes lukis as a way of remaining with friction—of writing again on surfaces that were never meant to be rewritten, and listening to what continues to speak beneath damage, beneath beauty, and beneath silence.