Stanislava Pinchuk Loops Through Time

23 May 2025

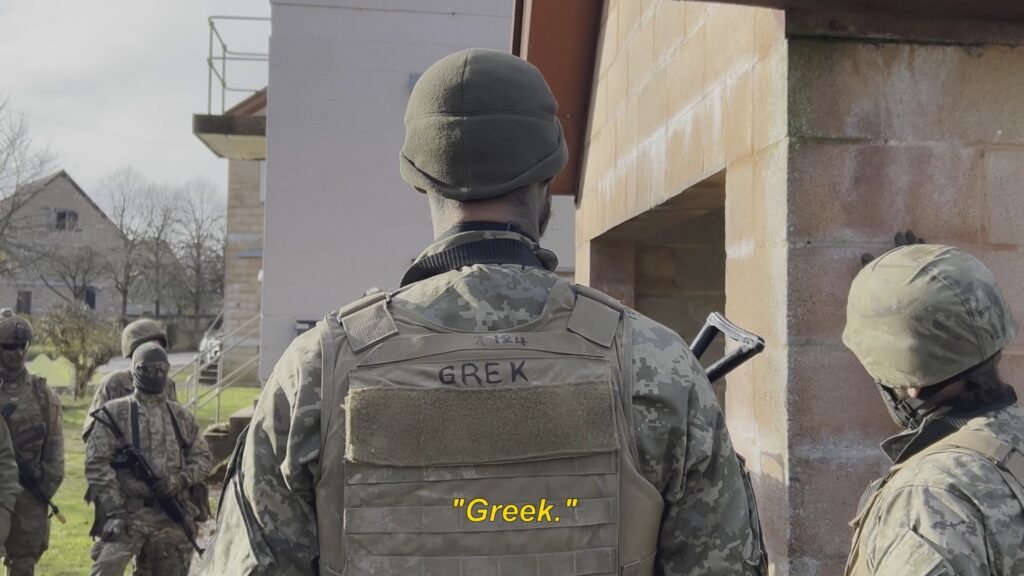

Stanislava Pinchuk was deployed to observe combat training for the Armed Forces of Ukraine in November 2023 as the Official War Artist of Australia. In this position, commissioned by the Australian War Memorial, she was to document and reflect on Operation Kudu, a mission of Australian soldiers which trains Ukrainian recruits in trench, woodland and urban warfare in a facility in southern England.

An Australian-Ukrainian artist born in Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine, Pinchuk has been creating works engaged with the scale, history and legacy of geopolitical conflict since 2015. The earliest of these include series of data maps made with pin-holes on paper studying the topographical changes of conflict sites around the world, from areas of invaded Ukraine to the Fukushima Daiichi and Chornobyl Nuclear Exclusion Zones, and the destroyed Calais ‘Jungle’ Migrant Camp in France. Works made during and after Pinchuk’s deployment, including most recently at the Vila 31 x Art Explora Residency in Tirana, continue the artist’s interest in articulating the personal, narrative, aesthetic and ethical dimensions of the geopolitical stage.

Stanislava Pinchuk in her studio, courtesy of the artist.

In her deployment, Pinchuk was placed in a rotating group of around 150 soldiers and recruits, all men, with an average age of 35, exactly her age at the time. The training was “super-fast, superhuman”, Pinchuk says, describing her documentation of the experience on film, the result of which will be shown with the Australian War Memorial as an upcoming commission. “The stipulations of the invitation were very generous, so much so that I added my own rules for how I wanted to approach my response. I wanted to make a record in which all the participants on site — the soldiers, cleaners, kitchen staff, translators, everyone — could see themselves; and make work that could become part of a rigorous historical record, beyond what I feel in this moment. I keep asking myself: how would this work sit 100 or 200 years from now?”

Alongside shooting footage, Pinchuk produced a series of 35 mm photographs of the soldiers in her unit, which had to be manually blurred to protect the identities of their subjects from “not only the public eye, but also from enemy facial-recognition technologies”. For the artist, the photographs altered by her painterly, hand-done erasures, began to resemble “ghost images”, forming a series that came to be titled, Each Apparition, Searches for an Eye.

Stanislava Pinchuk, A 12; H 95; A 01, H 92; B 28, A 16, 2025, Perspex-mounted pigment print, erasure and stainless steel, 26 x 20 x 6 cm (frame size), 4.5 x 3.5 cm (photograph size)

“In the 19th Century, photographers thought they were — and in a sense, they truly were — capturing ghosts on long exposure photographic plates,” Pinchuk explains. “My photographs of the soldiers, whose faces I am obligated to obscure, capture spirits in a kindred way. In the erasure process, I tried to hide as little as possible so as to keep some of the intensity of each photograph, some presence of the person and the energy of the moment. But within this iconoclastic process, I also had to commit each, now-hidden face to my own memory. It’s the double bind of the photograph, the flux and re-flux of the image; for it to become public, to become a part of a record for the moment, it has to become destroyed in part. It makes me think of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in which he wrote that a photograph is an invitation for us to attend our own absence. In these photographs, I suppose I am also attending my own absence; of when I was behind the camera, outside of the moment in order to capture it.”

Pinchuk’s deployment experience features most prominently in the central channel of her recent three-screen video work The Theatre of War (2024), which will be on view as a finalist of The Ramsay Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia (30 May – 31 August 2025), after having been shown at the National Gallery of Kosovo (curated by Valentine Umansky, Tate Modern), Dallas Contemporary Museum of Art (curated by Lilia Kudelia), Ames Yavuz Sydney (MEMORY/MYTH, curated by Ananya Mukhopadhyay) and ACMI (curated by Fiona Trigg).

Installation view of Stanislava Pinchuk, The Theatre of War, 2024, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, curated by Fiona Trigg.

Anchoring the film installation, is the central screen, in which we see Ukrainian soldiers in the depths of their combat training in a simulation ground in southern England. With a history of serving as training site for the international peace-keeping corps for Bosnia and Herzegovina & Kosovo since the 1990s, many of the ground’s buildings are an uncanny duplitechture of the Balkans, set against a pastoral British landscape. Pinchuk’s camera rests as attentively on this setting as on its players, the practice stage for the ‘theatres of war’ as understood by the military, as any geographical areas involved in combat operations. “The deployment is a practice, but it’s nevertheless a rehearsal for something very real,” Pinchuk says.

Across all three channels of the film, we hear recitations of the first seven lines of Homer’s Iliad, the epic poem of the Trojan War. To the left of the soldiers, Pinchuk takes us to a theatre stage in Sarajevo, on which a polyphonic choir practices, and then delivers the lines as a song of lament. An important venue of cultural resistance during the Siege of the city in the 1990s, held by the citizens of the city despite an attempted capture, the stage hosted vital cultural programming in Sarajevo at the time, including performances by traditional folkloric ensembles and the Pageant for Miss Besieged Sarajevo, with Susan Sontag’s renowned production of Waiting for Godot staged nearby.

Stills from Stanislava Pinchuk, The Theatre of War, 2024, Channel 1, 3m35s; Channel 1, 7m08s; Channel 2, 3m43s; Channel 2, 4m27s.

In contrast, the film’s third channel unfolds on the supposed tomb of Homer and his mother Klimene, on the island of Ios in Greece, looking out to the sea where the original stories of the The Odyssey and Iliad took place, “where they linger like ghosts over the water… where these words lived and evolved through mnemonic recitation, centuries before any written form was made,” says Pinchuk. Two local high school students, “custodians of this tradition”, sit on the tomb in the early hours of the morning and recite the epic in modern Greek, as they are taught to memorise in the classroom.

“When I was younger, the age of the students in the film, I thought time was linear,” says Pinchuk, reflecting on the layered staging of stories in the work. “I don’t know if it’s war, or the state of the world, or just getting older, but time feels circular now, made of loops of signifiers and repetitions. This feeling naturally enters every work I make, no matter the medium, in one way or another.”

Stills from Stanislava Pinchuk, The Theatre of War, 2024, Channel 3, 8m24s; Channel 3, 2m51s.

Pinchuk’s attunement to the patterns of time and history also comes in the wake of a freshly completed three-month residency at Vila 31, the former home of dictator Enver Hoxha in Tirana, Albania. “I was the first artist to sleep in the Vila,” she says. “The first night, I was completely alone in this huge, empty mansion. I couldn’t sleep. I just sat in every room and thought about my grandparents, my great-grand parents, and what they witnessed and survived. I thought about the women in my family and what they lived through—Holodomor, Ukraine’s War of Independence, World War II, Communist occupation and its fall. I thought of my great-aunt who entered the military then and saw myself somehow being in a similar loop of time. I thought about the ideological lines and political systems that they saw come and go. About what this Vila had seen. And why would I think that my lifetime will be any different?”

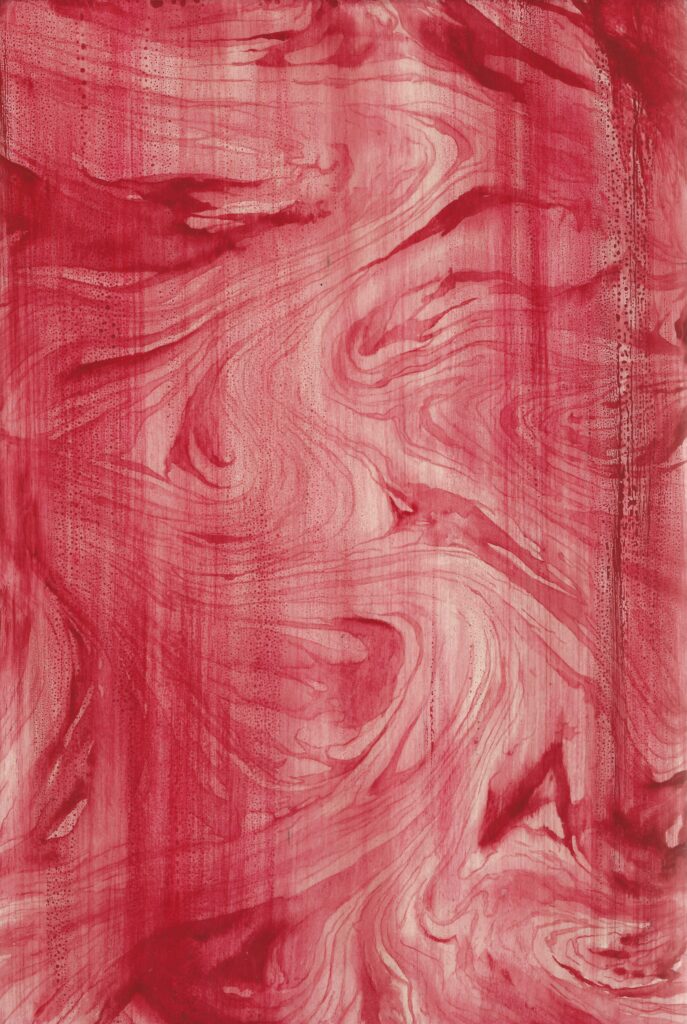

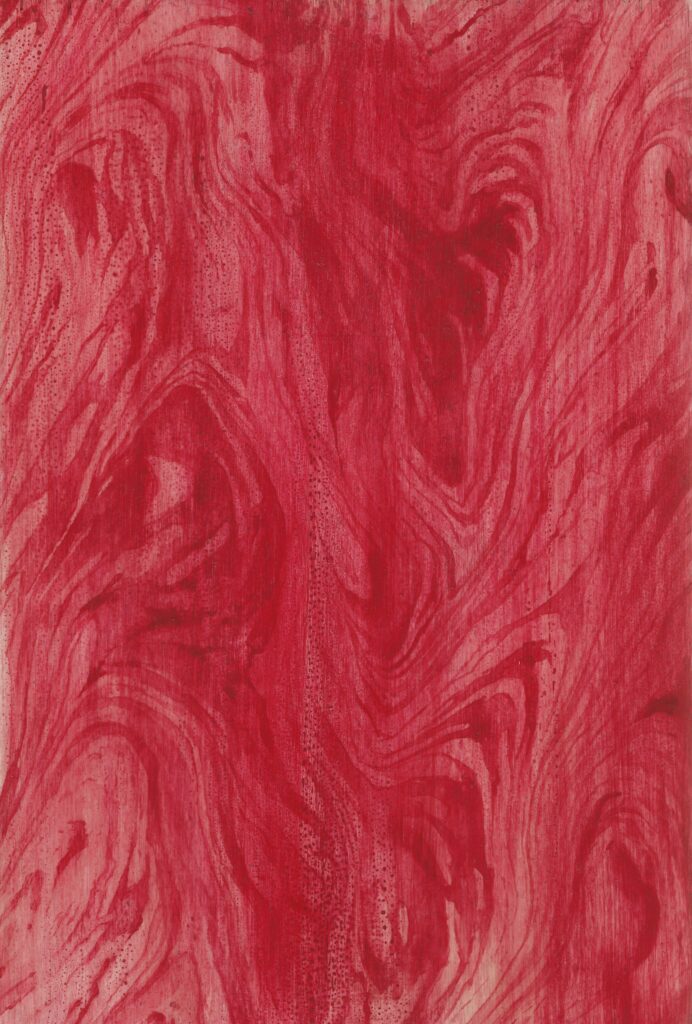

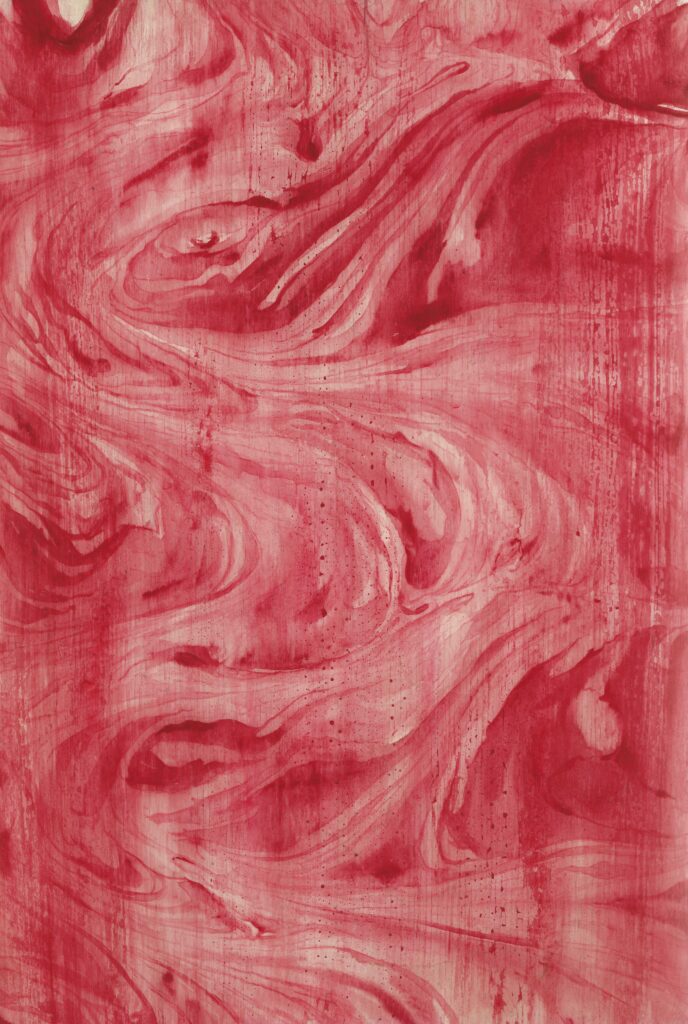

The circulation of monumental ideologies and their totalitarian violence — “their blood” — became the subject of Pinchuk’s work in Tirana, which she refers to as her Vampir series. While in Hoxha’s house, responsible for converting Albania into a one-party communist state under which thousands were imprisoned, exiled and executed, Pinchuk discovered a list of his private library of 22,000 to 30,000 books, most of which were banned for Albania’s citizens and appeared to have been confiscated in part from purged Party elites. “The library felt like a vampire’s corpse, formed on destruction” the artist says. “When I opened his collection of Karl Marx’s writings and saw the ebru marbling on its inside covers in clotted, dark red and sickly yellow, I felt like I just witnessed a murder, the violence of this history and ideology. I instantly snapped the book shut. It was so confronting.”

This library, its contents and this first impression are the inspiration for a new set of paintings by Pinchuk, made loosely in the socialist realist style dominant in Hoxha’s time, an obligation forced unto artists of such regimes.

Stanislava Pinchuk, Study: ( Inside Front Cover 1 ) Karl Marx, Œuvres Politiques IV : Paris, Ancienne Librairie Schleicher ( A. Costes, editor )1929; Study: ( Inside Back Cover 1 ) Karl Marx, Le Capital VIII : Paris, Ancienne Librairie Schleicher ( A. Costes, editor )1930; Study: ( Inside Back Cover 2 ) Karl Marx, Le Capital XI : Paris, Ancienne Librairie Schleicher ( A. Costes, editor )1946, 2025, Gouache on wood, stainless steel, 20 x 30 cm.

“It’s about these loops of time, the stories are obscured and found,” Pinchuk says. “The photographic plates that make up Each Apparition, Searches for an Eye are as much about the 19th Century, the first war photographs, as about what the war portrait has become in the 21st Century. Both the Vampir series and The Theatre of War are about the links between these monstrous centuries too: the 19th Century genre of the vampire novel as an ostracisation of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, and of the Homeric question so often posed by academics then, which also interrogated the region in its own way. It’s all about the veil, the curtain, the lens, the word, the eye — the parts are all there, they are just being rearranged in each work, and by the moving hand of history.”

Stanislava Pinchuk’s The Theatre of War (2025) will be on view at The Ramsay Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide from 30 May – 31 August, 2025.

Each Apparition, Searches for an Eye, a solo exhibition by Stanislava Pinchuk takes place at Ames Yavuz Sydney from 1 June – 12 July, 2025.

Studies for paintings for the Vampir series by Stanislava Pinchuk are included in a group exhibition, Polyphonies at Ames Yavuz London from 6 June – 26 June, 2025.